Examples

A number of examples are provided for those that hate reading. The input of the program is similar to EBNF with an extra feature for repetition.

Diagrams and sequences

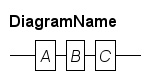

DiagramName : A B C

;A diagram starts with its name, a colon, the syntax that should be shown (in this case the sequence A, B, C), and finally, a semicolon as terminator. This gives the following result.

As rail diagrams are read from left to right, following a line without taking a sharp turn, the resulting image is not a surprise.

Choices

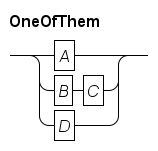

The second primitive is choice, where you pick one of the given alternatives. As with EBNF, this is written with the pipe symbol |, like:

OneOfThem : A | B C | D ;This results in:

Note that as sequence has higher priority than choice, the B and C sequence forms one alternative. You can use parentheses to break the priority chain, e.g.:

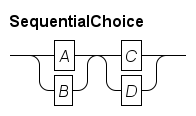

SequentialChoice : ( A | B ) ( C | D ) ;This gives a sequence of choices:

Optional

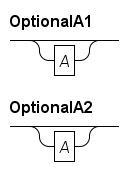

An optional part of the syntax can be described in multiple ways:

OptionalA1: () | A;

OptionalA2: A? ;This results in:

The dedicated optional syntax (?) is often more convenient than using the choice syntax.

Repetition

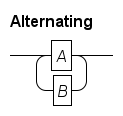

The core repetition primitive is alternating between two nodes:

Alternating : A + B ;This results in:

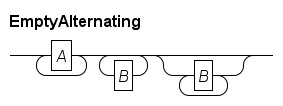

You can make one (or both) of the paths empty, which results in the normal EBNF repetition semantics. Below, node A must occur at least once, while node B may also be skipped.

EmptyAlternating : ( A + () )

( () + B )

( () | ( B + () ) ) ;This gives:

The third repetition is an alternative for the B sequence. It avoids the caveat with repetition due to the right-to-left visiting order of the bottom path, made more clearly visible in the following example:

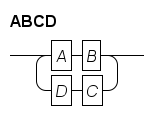

ABCD : (A B) + (C D) ;It results in:

It describes EBNF AB(CDAB)*, and the tool translates it correctly, but the bottom path does not read nicely, as you have to read that part from right to left.

It is advised to avoid this case by changing the diagram. Limit the second part of the + operator to one node, possibly by introducing an additional non-terminal.

Splitting long sequences

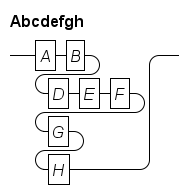

For rules that have a long sequence, the width of the diagram grows quickly beyond the width of the page. The best way to deal with that is to change the diagram, for example by moving a part of the sequence to a new non-terminal.

The program however does offer a quick fix around the problem at the cost of a less readable diagram. An example is shown below:

Abcdefgh : A B \\

D E F \\

G \\

H

;This gives:

The double backslash breaks the ‘line’ and it continues below on the next line. You cannot break the empty sequence, and each row must have at least one node.

Referencing a path in the diagram

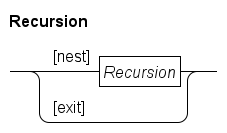

When explaining a diagram, it can be useful to refer to a path in the diagram. The program has a bracketed string for that:

Recursion : [nest] Recursion

| [exit] ()

;

Now you can say that the [nest] path recursively applies the rule, while the [exit] path ends the recursion.

Terminals

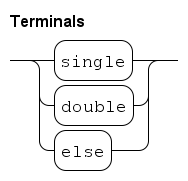

Until now, all names in the diagrams have a rectangular box around them which means (by default) it is a non-terminal. The name used in the diagram input file is also the name displayed in the output.

Terminals in the diagram do not have a name, but show the concrete syntax instead. The simplest way to write a terminal is shown in the first and second alternative. They state the literal concrete syntax of the terminal surrounded by single or double quotes. The third alternative introduces the internal name OTHER for the terminal and uses the properties file to translate the name to the actual syntax for that name.

Terminals : 'single'

| "double"

| OTHER

;Fragment of the properties file related to this diagram that says the terminal named OTHER should display else in its box:

terminal.token.OTHER: elseAnd the generated output is then:

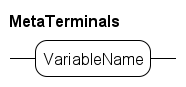

Meta-terminals

While grammars only have terminals and non-terminals, we found use for a third form in explaining the syntax of a language. In almost every language a few non-terminals are too trivial or too large to define precisely in a rail diagram. Common cases include literal numbers, literal strings, and sets of names that can be used for identifiers. Instead of defining the syntax of such a non-terminal in a diagram in full detail, the accompanying text of a diagram can define it in a few compact sentences. Such non-terminals thus have no defining rule and also no concrete syntax. We name these hybrid forms meta-terminals.

They are added in the diagram much like the third alternative above. A name is given to it in the diagram input file, and the properties file defines the associated displayed text. For example:

MetaTerminals : Identifier

;Fragment of the properties file related to this diagram stating the displayed text should be VariableName:

meta-terminal.token.Identifier: VariableNameAnd the generated output is then:

The text around the diagram should describe the allowed syntax of VariableName.

Meta-terminals have a rounded box around the name indicating lack of a definition elsewhere, but use the non-terminal font for its name indicating the written name is not taken to be as the literal text.

Further reading

In this section a hands-on explanation was given to get started making diagrams without spending a lot of time grasping all the details.

In the Grammar section the grammar of the rail diagram is explained in more detail.

If default behavior is not to your liking, layout and many other settings can be overridden in a properties file, see the Customizing output section for details.