Synthesis-based engineering example

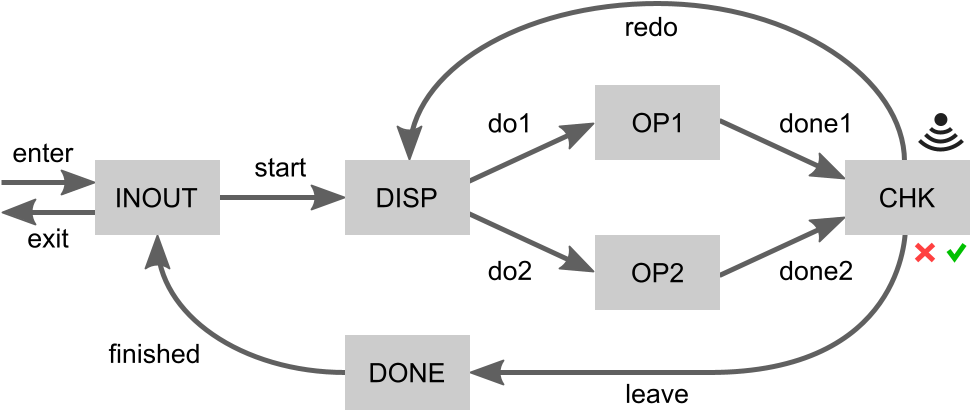

To demonstrate the value of synthesis-based engineering, let’s look at an example. The following figure illustrates an example manufacturing system that processes products:

Products enter at the INOUT place. From there production can start by moving them to the dispatcher (DISP). The dispatcher dispatches a product (do1 or do2) to one of two operators (OP1 or OP2) that perform the same operation. Once the operation is completed (done1 or done2), the product is moved to the checker (CHK). The checker determines whether the operation has completed successfully or has failed. If it has failed, the system must redo the operation on that product. This may be repeated until the operation is successful. The product must then leave the processing loop, moving to DONE. It is then finished and moves back to INOUT. There it may exit the system.

The gray boxes indicate places where at most one product can be located at a time. The moving of products through the system is visualized by the labeled arrows in the figure. Each arrow corresponds to an actuator under the control of the controller. The controller can thus decide when to move products from one place to another. A sensor indicates the result of the check performed on processed products, indicating whether they are OK or not. This sensor works autonomously and is thus not controlled by the controller.

FIFO requirement

The example system, without any controller that controls it, already ensures that:

Products that enter can only start, preventing them from exiting without having been processed.

Products that failed processing must redo the operation.

Successfully processed products must leave the operation area.

Once a product passed finished it must exit, preventing it from being processed again.

For this example, we consider only a single requirement:

Products must enter and exit the system in FIFO order.

That is, if one product enters earlier than another, it must also exit earlier.

Without additional control, the system does not satisfy this requirement, as it is possible for multiple products to enter the system and subsequently be processed concurrently. Then, if a later product finishes the operation earlier, or the earlier product requires rework, the later product may be done sooner and thus exit the system earlier. The controller must restrict the behavior of the system such that it satisfies the requirement. It can only do so by controlling the movement of products through the system.

The FIFO requirement is specified in natural language as a short and simple sentence. It can similarly be quite easily modeled, by tracking the order that products enter and exit the system. Each product that enters the system is given a unique identifying number, one higher than the previous product. As products exit the system, the identifier of the last product that exited the system is stored (lastExitId). When a product is about to exit the system, it is in the INOUT place. If the identifier of the current product on the INOUT place is given by curId, then the requirement can be formulated as:

curId = lastExitId + 1

See the section on synthesis-based engineering in practice example section for how the example system and its requirement can be modeled in CIF.

Synthesis-based engineering

There are various ways to ensure the FIFO requirement holds. A silly solution is to never allow products to enter the system. As there are then no products in the system, products also never leave the system. Therefore, all (non-existent) products are in FIFO order. Another slightly more useful option is to only allow a single product to be processed at a time. This would however severely limit the productivity of the system. It is actually not that trivial to decide the exact conditions under which the products may move, while still ensuring the FIFO requirement is satisfied.

We can however automatically compute the conditions that must hold for each movement by applying supervisory controller synthesis. This computes for each movement the minimal restriction that must be applied to enforce the requirement. Through synthesis, we obtain a supervisory controller that restricts four movements:

Movement start is only allowed if one of the following two conditions holds:

At the DISP place, OP1 place, OP2 place, and CHK place, there is in total at most one product.

At the DISP place, OP1 place, and OP2 place, there is in total at most one product. There is also a product at the CHK place and the check indicates the product was successfully processed.

Movement done1 is only allowed if the following two conditions both hold:

Either there is no product at the DISP place, or it is a later product than at the OP1 place.

Either there is no product at the OP2 place, or it is a later product than at the OP1 place.

Similarly, movement done2 is only allowed if the following two conditions both hold:

Either there is no product at the DISP place, or it is a later product than at the OP2 place.

Either there is no product at the OP1 place, or it is a later product than at the OP2 place.

Movement enter is only allowed if less than four products are in the system.

But why are these the 'optimal' restrictions?

It is important to realize that:

If a product is checked and found to be successfully processed, it can only leave. It can not be reprocessed (redo). If a product is moved to CHK too early, a product that should exit the system before it can’t overtake it anymore. This could lead to a violation of the FIFO property if another product that must exit earlier is for instance still being processed.

Only at most two products may be in the processing loop at any time. That is, at most at two of the DISP, OP1, OP2 and CHK places there may be a product, at any time. This way, if a product keeps failing to be processed successfully, it can be redone over and over again, while the other product is at one of the operators. With three or more products in the processing loop, this is not possible. An exception to 'at most two products in the processing loop' rule is when a product has been checked and found to be successfully processed. Then, a third product may be present, as the successfully processed product can then leave the processing loop and at most two products will remain in the processing loop.

Then the supervisor restrictions are quite logical:

The first restriction indicates when a product may start processing. Either one of its two conditions must hold for the start movement to be allowed. This directly follows from realization B. The first condition follows from the 'at most two products in the processing loop' rule. At most one product may be in the processing loop for another to enter it. The second condition describes the exception to this rule. There may be two products in the processing loop if one of them is a successfully processed product about to leave the processing loop.

The second and third restrictions indicate when a product may move to be checked. These two restrictions follow directly from realization A. A product X may only be moved to be checked, if there is no product that must exit earlier. Obviously, moving a product to the checker is physically only possible if there is a product at an operator, as otherwise there is no product to move. Also, it is only physically possible to move a product to the checker there is not already a product at the checker, as each place can only hold one product. This leaves only the dispatcher and other operator as places to be checked. If there would be an earlier product at the dispatcher or other operator, such a product would not be able to overtake the product about to be moved to the checker, leading to a violation of the FIFO property. Hence, both restrictions have to conditions, on for the dispatcher and one for the other operator. Either there must be no product at those places, or it is later product.

The fourth restriction indicates when a product may enter the system. It only allows a product to enter if there are less than four products in the system. This means that the restriction ensures that at most four products are in the system at any time. Through realization B we know at most three products may be in the processing loop. Then only at most one of the INOUT and DONE places may contain a product, for a total of four products in the system. To understand why this is the case, consider the following:

A product could be at the INOUT place. But then no product must be at the DONE place. If there were a product at the DONE place, there would be products at the INOUT, DONE and CHK places. The product at the CHK place could then not move to the DONE place, as that already has a product. Similarly, the product at the DONE place could then also not move to the already occupied INOUT place. And the product at the INOUT place could then not move to the DISP place, as the processing loop is already maximally filled. This would mean no product could move anywhere. This kind of deadlock is prevented by the fourth condition.

A product could be at the DONE place. But then, by similar reasoning, no product must be at the INOUT place.

All of this is certainly a lot to consider! Would you have been able to figure all of this out by yourself? And how long would that have taken you? Considering this is only a simple example system with only one non-trivial requirement, it is clear that having some computer assistance when engineering a more realistic controller can be very useful.

Example benefits of synthesis-based engineering

Finally, let us consider some of the benefits of synthesis-based engineering as it relates to this example:

Synthesis automatically computes the optimal control conditions. It should now be clear that this can save a lot of effort.

Manually engineering the controller can be quite tricky. It could easily lead to mistakes if certain scenarios are not properly accounted for. For instance, a restriction could be missed, or one of them could be incorrect. Synthesis can thus also reduce human error.

Through synthesis you only have to specify the requirement and synthesis automatically generates a correct-by-construction controller, from which you can automatically generate the implementation. For the simple to specify but difficult to implement example requirement, this allows you to focus on what the controller should do (the requirement), rather than how the controller should do this (the complex control conditions and their implementation).

As an alternative to synthesis, we could apply formal verification on the system model to check whether the FIFO requirement holds. However, as the requirement does not hold on the system without a controller, we would get only a counter example representing a scenario indicating where the requirement does not hold. Likely, it would take several iterations and quite some thinking to manually arrive at the exact correct control conditions. Compared to formal verification, synthesis produces all the correct control conditions, automatically and in a single iteration.

An engineer that develops the controller manually, may well impose severe restrictions to avoid much of the complexity of satisfying the FIFO requirement. The control conditions produced by synthesis however, are minimally restrictive. Products may enter the system, start processing, be processed in parallel, and leave the processing loop, whenever possible. This ensures the maximum throughput of the system can still be achieved.

Synthesis-based engineering allows for a modular design. The various parts of the system, as well as the requirement, can be modeled separately. This makes it easy to adapt the system (model), to for instance allow products that do not require processing to bypass the processing loop. With minimal changes to the system model, and no changes to the requirement, a new supervisor can then be produced by the push of a button. This allows for incremental development of the system and its controller.

And again, consider that this is only a simple example system, with only a single requirement. Synthesis-based engineering has even more value when multiple, complex and related requirements need to be considered, or when controllers for many similar yet different systems need to be developed. See the section on benefits of synthesis-based engineering for further benefits of the approach.

Even though synthesis-based engineering has many benefits, companies should not underestimate how significantly different it is from traditional engineering. They should consider and manage the challenges particular to this engineering approach.