Channels

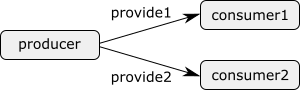

Consider the following figure of a producer and two consumers, where rectangles represent entities and the arrows represent the data that is communicated:

The producer creates products, identified by a unique identification number. Each product produced by the producer, is provided either to the first or to the second consumer. Consider the following CIF specification:

event provide1, provide2;

automaton producer:

disc int nr = 0;

location:

initial;

edge provide1, provide2 do nr := nr + 1;

end

automaton consumer1:

disc list int nrs;

location:

initial;

edge provide1 do nrs := nrs + [producer.nr];

end

automaton consumer2:

disc list int nrs;

location:

initial;

edge provide2 do nrs := nrs + [producer.nr];

endThe producer keeps track of the identification number (variable nr) of the current product, and provides products to either the first consumer (event provide1) or the second consumer (provide2). Both consumers have a list of their products (variable nrs in the consumer automata). Initially, the consumers don’t have a product, and the list is empty. When a consumer gets a new product, it looks up the identification number of the product at the producer, and stores it locally. The producer then moves on to the next product, by increasing its current identification number.

We can identify two problems in this model.

The first problem is that we need two events in order for the producer to provide products to either the one consumer or the other consumer. If we used only one event, both consumers would need to use that event, have the event in their alphabet, and would thus have to simultaneously participate in the synchronization. A consequence of having an event per consumer, is that the producer automaton has both events on its edge. Adding a third consumer entails having to add another event, as well as having to modify the edge of the producer automaton. This is not a nice scalable solution.

The second problem is that the consumer refers directly to the nr variable of the producer automaton. This introduces a very tight coupling between the producer and the consumers. It exposes the nr variable of the producer to the consumers, making it more difficult to change the producer without changing the consumers.

Both these problems can be solved by using channels. Channels are a special form of events, that can be used to communicate or transmit data from a sender to a receiver. In our example, data that is communicated are the identification numbers of the products, the producer is the sender, and the consumers are the receivers.

Channels require one or more potential senders, and one or more potential receivers. Automata cannot be both sender and receiver for a single channel. They may however be a sender for one channel, and a receiver for another channel. For every transition, exactly one of the senders and exactly one of the receivers participate. The sender sends a value, and the receiver receives that value. This type of communication is often called channel communication or point-to-point communication, as the data is communicated from one point (the sender) to another point (the receiver).

Multiple automata that synchronize over the same event perform a transition together. Similarly, a sender and receiver that together perform a channel communication, perform a transition together. In both cases, all automata involved take their respective edges synchronously (simultaneously).

Channels are ideally suited for modeling product flows, or more generally the movement of physical entities through a system. Physical objects usually don’t duplicate themselves or spontaneously stop to exist. This fits nicely with channels, where data is communicated or passed along from exactly one sender to one receiver. In our example, product produced by the producer are physically provided to one of the consumers.

The following CIF specification models the above example using channels:

event int provide;

automaton producer:

disc int nr = 0;

location:

initial;

edge provide!nr do nr := nr + 1;

end

automaton consumer1:

disc list int nrs;

location:

initial;

edge provide? do nrs := nrs + [?];

end

automaton consumer2:

disc list int nrs;

location:

initial;

edge provide? do nrs := nrs + [?];

endThe provide1 and provide2 events have been replaced by a single channel named provide. Channels are declared similar to events, but have a data type that indicates the type of values that are communicated over the channel. In this case integers are communicated.

The producer now uses the channel on its edge, instead of the two events. The exclamation mark (!) after the channel name means that the producer is sending over the channel. After the exclamation mark, the value that the producer sends is given. In this case, the producer sends the identification number of its current product.

The edges of the consumers have been modified as well. The channel is used with a question mark (?) after the channel name, indicating that the consumers receive over the channel. The received value, which is available as the ? variable in the update, is directly added to the nrs list of the consumer.

By using channels, we no longer need multiple events, and the producer does not need to be modified if another consumer is added. This makes the model scalable to varying amount of consumers. Furthermore, the consumers now use the ? variable to obtain the received value, and no longer need direct access to the variables of the producer. This makes it easier to modify the producer without having to also modify the consumers.

To conclude this lesson, we’ll extend the example with a second producer:

event int provide;

automaton producer1:

disc int nr = 0;

location:

initial;

edge provide!nr do nr := nr + 1;

end

automaton producer2:

disc int nr = 0;

location:

initial;

edge provide!nr do nr := nr + 1;

end

automaton consumer1:

disc list int nrs;

location:

initial;

edge provide? do nrs := nrs + [?];

end

automaton consumer2:

disc list int nrs;

location:

initial;

edge provide? do nrs := nrs + [?];

endThe producer automaton has been renamed to producer1, and a producer2 has been added. Both producers independently produce products and provide them to the consumers. Both consumers can receive products from either producer. At all times, four transitions are possible: producer1 communicates with consumer1, producer1 communicates with consumer2, producer2 communicates with consumer1, or producer2 communicates with consumer2.

Note that the producer1 and producer2 automata are identical, as are the consumer1 and consumer2 automata. In the lesson on automaton definition/instantiation, it is shown how this duplication can be prevented.