This pattern centers around the idea to delegate the data transmission to external services, by-passing the Ditto cluster, while still being able to benefit from Ditto’s policy system and IoT architecture.

Context

You have services exposing their functionality transparently though Ditto’s messaging API as part of your digital twin. E.g. a history service providing the actual interface to your timeseries database as part of the things interface such that a client may not need to know if the history actually is managed by the thing itself or any other program. You use Ditto’s policy system to secure access to your services that way.

Your services provide data in quantities that are not suited for transmission through the Ditto cluster directly, because of (de-)serialization costs, round-trip-times etc.

Problem

You want to query a greater amount of data (e.g. database query result) by issuing a Ditto message to a thing which is picked up by a service speaking with you databases. It does not work to just let this service return the result as a response to the Ditto message, since the messaging system in the Ditto cluster is not designed for big quantities of data and will reject them based on tight quotas. Also the costs due to many (de-)serialization steps are high.

Solution

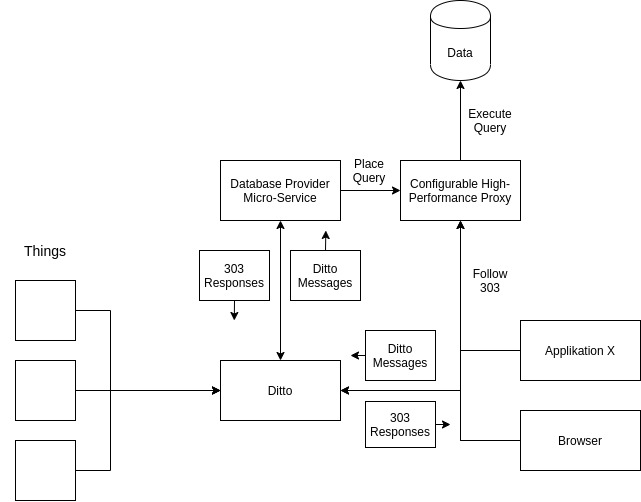

The solution consists of the following systems:

- database: where your bigger chunks of data reside and wait to be delivered / queried

- database provider mirco-service: the service managing the database connection and exposing it to clients through things messaging API

- thing: a digital twin with extended API through a micro-service

- client: a client-application trying to receive bigger quantities of data via a things messaging API in the scope of that thing and secured via ditto policies

- high-performance data proxy (or just proxy): a third-party application proxy sitting in-between the database and the provider micro-service managing data delivery

In order for the client-application to retrieve the requested data in a secure and performant way we introduce a high-performance proxy (e.g. based on nginx, example below). The proxy will not have any credentials by itself, it’s just serving prepared queries on a randomly, hard-to-guess URL with an expiration time of 5 minutes. It features an admin API which the micro-service has credentials to access.

The provider micro-service hooks into a twin (e.g. via websockets) and listens for queries. If a query arrives it will formulate the query, store it at the high-performance proxy (which might already query the data) and return a randomly generated URL to the proxy together with a Location-header as a response to the client-application. The client then needs to follow the response in order to retrieve the data from the proxy.

With this approach the access to the database is secured via Ditto policies and in scope of single things while the data retrieval happens via a performant proxy application without the Ditto cluster ever seeing those packages.

Note: Keep in mind that security in this situation is highly dependent of the micro-service implementation. You have to make sure that your implementation uses provided information of ditto properly and that the contents of a message do not allow a violation of the policy. E.g. through SQL-Injections.

Discussion

Benefits:

- Higher performance compared to using just Ditto

- The Ditto policy system can be utilized to scope and secure data access from clients to databases/-stores

Drawbacks:

- A third-party application for the high-performance proxy has to be added and maintained

- A custom messaging API is necessary in the first place introducing a higher complexity

- A translation of certain query-languages from messages to the actual databases / applications has to be implemented

Issues:

- Managing and communicating custom messaging APIs is not natively supported in Ditto, other ways have to be explored to keep APIs consistent

Policies

Policies can be used to restrict access to the provider micro-service and through that eventually to the database using

restrictions on the message:/ resource.

Let’s assume that the provider micro-service registers via websockets and expects requests to the message-topic

/services/history. With the following policy entry we can allow access to this resource:

{

"subjects": {},

"resources": {

"message:/": {

"grant": [],

"revoke": ["READ", "WRITE"]

},

"message:/inbox/messages/services/history": {

"grant": ["READ"],

"revoke": []

},

"message:/outbox/messages/services/history": {

"grant": ["WRITE"],

"revoke": []

}

}

}

The first resource entry revokes any access to messages for subjects of this type. This is optional. The next entry

allows the provider micro-service to read messages from the topic /services/history. Note that we’ve decided to insert

another “namespace” /services here to distinguish these messages from other device faced messages. The last section

than allows the provider micro-service to reply to the received requests with it’s 303 response.

This can also be built against single features. Since features have to be stated explicitly in the policy, this is not as general but can provide a more fine-grained access control when using distinct policies for different things, or features with same names over multiple things.

Proxy Implementations

The ceryx proxy project was used for the PoC (or reference implementation) of this pattern. It was enhanced with delegation features which still have to be contributed upstream. Have a look at the forks source code or the corresponding container image until then.

The ceryx proxy is a modified nginx with a redis-database to store the randomly generated IDs correlating with prepared queries. It is not suited for this use-case on its own so capabilities to store queries (including Authentication) behind expiring random URLs was added, but not send upstream yet.

Known uses

othermo GmbH uses this for a history-service: The history service connects to Ditto via

websockets and hooks into things by answering specific /history messages. The messages API is translated to InfluxDB queries

which then are stored with a randomly generated URL and expiration of 5 minutes at the high-performance proxy.

The service then returns the random URL to the client which then follows the 303 to retrieve the actual data.

The messages contain InfluxDB-similar query elements while the query is only constructed at the provider service. That’s because the provider service uses the databases specifics like Tags in InfluxDB to assign thingId, policy and path information in order to get the stored data into the right scopes and to be able to retrieve the correct sets of data.