Model-based engineering

Model-based design, model-based software/system engineering and model-driven engineering, are related terms. They place models at the center of the entire development process and the entire lifecycle of the system, including design, implementation and maintenance. The models fill the gap between the specification and implementation.

Model-based engineering process

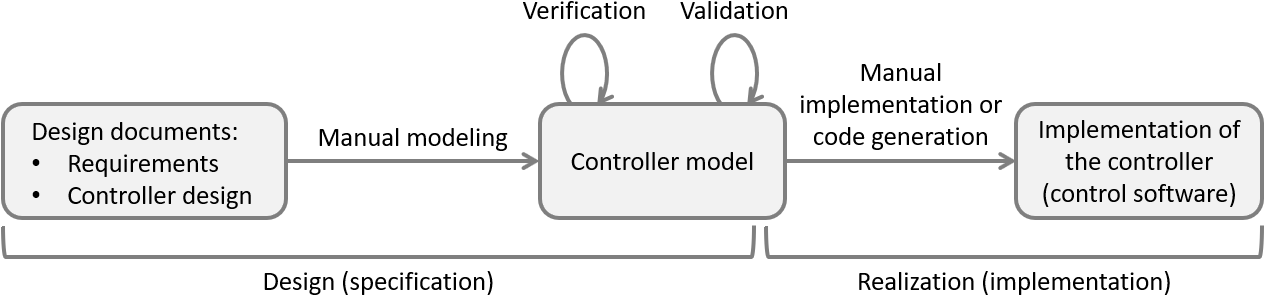

The following figure shows a simplified development process for model-based engineering of supervisory controllers:

At the center is a controller model, a model of a controller that unambiguously specifies how the controller works. It precisely specifies how the state of the controller changes when a sensor signal changes, and under what conditions and in which states an actuator may be turned on or off. Ideally, the model has a mathematical foundation. It may for instance be modeled as one or more state machines.

The controller model is manually modeled from design documents. They for instance list the functional and safety requirements of the controller, describe its control states and indicate when it should actuate the various actuators depending on changing sensor signals.

The controller model must be verified and validated. Verification involves checking and ultimately ensuring that the system, controlled by the controller, satisfies its specified requirements. Validation involves checking that the controller ensures the desired system behavior, and thus ensuring it is the desired controller. Since a controller must satisfy its specified requirements, this includes validating the requirements to ensure they are the desired requirements. This may be supported by formal methods, methods with a mathematical foundation, and supported by computer tools. For instance, a controller model may be simulated. This may reveal issues, that can be addressed to improve the controller model.

The control software is typically implemented using a programming language, such as PLC code for a PLC platform, or Java or C++ code for an industrial PC. This may for instance be done in-house within the company, by different teams or departments, or by a supplier. While manual implementation is possible, the code is often automatically generated from the controller model.

Benefits of model-based engineering

Model-based engineering directly addresses many of the downsides of traditional engineering:

- Unambiguous and intuitive specifications

-

It is important that the models are formal models, with a mathematical meaning (semantics). Examples of formal models are state machines to model controllers and logical formulas for model requirements. The use of such formal models leads to unambiguous interpretation of control requirements and controller behavior.

The use of the right formal language, in which control requirements can be specified in an intuitive manner is essential. This is where domain specific languages (DLSs) play a role. Such a language closely matches the world of the domain experts, such that they can directly write their control requirements in a notation that fits how they think about the system. This leads to readable and unambiguous specifications.

Besides specific to a domain, domain specific languages are also more restrictive in what you can write down than a general programming language. While this seems to be a limitation, it is actually their strength. Due to the limited number of concepts to consider, there are less different ways to model a system. This further reduces ambiguity, due to more consistency and simpler specifications.

- Bridges the multi-disciplinary specification/implementation gap

-

Using a good domain specific language, both domain experts and software engineers can understand and interpret the specification in the same way, regardless of their different backgrounds. Obviously, the language must be rich enough to properly describe all relevant aspects of the domain. It must also use a proper abstraction level.

- Complete and consistent specifications through computer-aided validation and verification

-

The use of unambiguous formal models has even more advantages, as it makes it possible for a computer to interpret and analyze the models. The limited concepts of the domain specific language help to do so efficiently and scalably. Computers can with formal methods, mathematical techniques, quickly and accurately analyze countless scenarios. This is a great advantage compared to traditional document reviews.

An example of this is verification by means of model-based testing. Instead of manually writing dozens or hundreds of tests, a computer can automatically generate thousands, millions or even more tests from the controller model. This allows covering much more behavioral scenarios, increasing confidence in correctness of the controller model and its implementation.

Another example of this is validation of the specification by means of simulation. Using simulation various execution scenarios can be examined, to give insight into the behavior of the system being controlled by the controller. This provides new insights that can be used to further improve the specification. Especially for complex situations, which are difficult to understand, this is of great value.

The use of computer-aided verification and validation often exposes issues in the specification. Model-based testing for instance, may find that a certain scenario was not considered during controller design, and therefore does not satisfy the requirements. The controller model may then be adapted and tested again. This allows to effectively and iteratively improve the design, leading to more complete and consistent specifications, and therefore to better quality controllers.

- Address issues early to reduce effort and costs

-

A great benefit of model-based engineering is that verification and validation can be done already during the earlier phases of development, rather than only at later phases such as implementation or testing. It is well-known in industry that the later a mistake is found and fixed, the higher the effort and costs to do so. In practice, implementations developed using model-based engineering approaches are often produced more efficiently and with less mistakes. Through automation, changes can be incorporated more quickly into the models, and these can automatically be analyzed again.

Furthermore, the benefit of discussions that may arise early on during the development process, for instance about how the specification must be adapted if it is found lacking, is not to be underestimated. It is of great value that so early on it is possible to discuss control requirements and the behavior of the system during unforeseen circumstances, such as when a sensor is defect.

- Efficiently obtain correct-by-construction implementations

-

After several iterations the confidence in the controller specification is sufficiently high, and thus the chance of incompleteness and inconsistencies sufficiently low, given the amount of effort and money that can reasonably be spent during the development process. The development process produces an implementation-independent model of the control logic, that during the realization can be implemented. This may be done by a different team or department within the same company, or even by an external supplier. The formal specifications can then serve as a contract with the third party, allowing for more control. They can also be used to perform acceptance tests on the implementation.

While the controller can be manually implemented based on the controller model, automatic generation of the control software is often a better choice. Automation prevents the kinds of subtle mistakes that humans make when they manually implement something, ensuring consistency between the specification and the implementation. Automation also improves efficiency. If the controller model is changed, with the push of a button a new correct-by-construction implementation can quickly be generated from it.

- Implementation-independent models separate design from implementation

-

Since a controller model is implementation-independent, there is a clear separation between design (specification) and realization (implementation). It allows generating implementation code for different platforms, such as industrial PCs or PLCs, with different programming languages, such as Java, C or PLC code, for 32 or 64 bits architectures, etc. Additionally, controller models are vendor-independent, allowing to for instance generate PLC code for PLCs from different vendors. It is also possible to switch to a different platform or vendor at a later time, or additionally generate code for other platforms or vendors.

- Up-to-date models are the single source of truth

-

Model-based engineering places models at the center of attention. It is the models that are adapted if they are functionally incorrect, have inconsistencies, or new functionality is required. Techniques such as model-based testing, simulation, and code generation all operate on the models. The models are therefore the 'single source of truth'. Contrary to documents, the models will be maintained. They remain up-to-date as they are the basis of all development during the entire life cycle of the system, including design, realization and maintenance.

The use of model-based engineering combined with computer-aided design through formal methods thus has many advantages. It allows for producing unambiguous, complete, consistent, and up-to-date specifications, leading to higher quality controllers at similar or even lower effort and costs. However, specific forms of model-based engineering, such as verification-based and synthesis-based engineering, can offer additional benefits.

Even though model-based engineering has many benefits, companies should not underestimate how significantly different it is from traditional engineering. They should consider and manage the challenges particular to this engineering approach.

Terminology

The following terminology is often used when discussing model-based engineering of supervisory controllers:

- Code generation

-

The automatic generation of correct-by-construction control software from a controller model.

- Control requirements

-

Properties that a system must satisfy, even if they are not satisfied in the uncontrolled system. Examples include functional and safety properties. They are called control requirements, or simply requirements.

- Control software

-

The implementation of the controller in software. For instance, PLC code for a PLC platform, or Java or C++ code for an industrial PC.

- Controller model

-

A model of a controller that unambiguously specifies how the entire controller works. Also called a supervisory controller, or simply controller, in control theory. It precisely specifies how the state of the controller changes when a sensor signal changes, and under what conditions and in which states an actuator may be turned on or off.

- Controller validation

-

The process of checking and ultimately ensuring that the system being controlled by a controller exhibits the desired behavior, and thus ensuring that the controller is the desired controller. Since a controller (model) must satisfy its specified requirements, this includes validating the requirements to ensure they are the desired requirements.

- Controller verification

-

The process of checking and ultimately ensuring that the controller satisfies its specified requirements.

- Domain-specific language

-

A modeling language with concepts specific to a certain domain. This can for be the domain of supervisory controllers with concepts such as plants and requirements, or the domain of office lighting systems with concepts such as lamps and occupancy sensors.

- Formal method

-

A method with a mathematical foundation, typically supported by computer tools. For instance, formal verification or supervisor synthesis.

- Model

-

An unambiguous representation of all relevant concepts, ideally with a mathematical foundation. For instance, a model of control requirements in the form of logical formulas, or a model of a controller represented as a state machine.

- Model-based development/engineering

-

Places models at the center of the entire development process and the entire lifecycle of the system, including design, implementation and maintenance.

- Modeling language

-

A language in which models can be specified, in an unambiguous way, and ideally also with mathematical foundation.