Traditional engineering

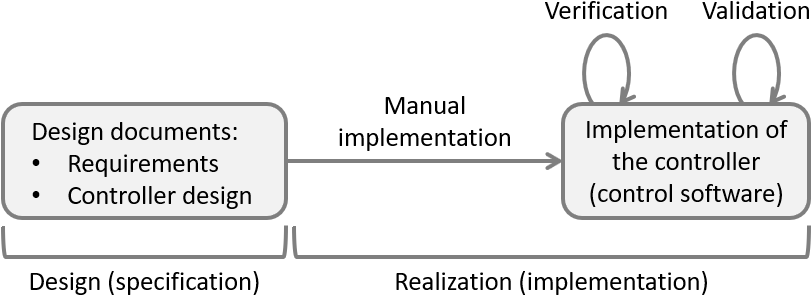

The following figure shows a simplified development process for traditional engineering of supervisory controllers:

Traditionally, controllers are first specified in design documents. They for instance list their functional and safety requirements, describe their control states and indicate when the controller should actuate the various actuators depending on changing sensor signals.

Subsequently, the controller is manually implemented in software code through the use of a programming language, such as PLC code for a PLC platform, or Java or C++ code for an industrial PC.

Finally, the implementation is verified and validated, typically by means of testing. Verification involves checking and ultimately ensuring that the controller satisfies its specified requirements. Validation involves checking that the controller exhibits the desired behavior, and thus ensuring it is the desired controller. Since a controller must satisfy its specified requirements, this includes validating the requirements to ensure they are the desired requirements.

Downsides of traditional engineering

Traditional engineering has been around for a long time. Companies typically know what works and what doesn’t, and how to work around the various challenging aspects of it. It can work well, particularly for small and simple systems, developed by a well-managed but small team. However, the approach has several disadvantages. These become especially apparent when applying it to develop controllers for larger and more complex systems, developed by multiple teams, or with some development activities outsourced to suppliers:

- Ambiguity

-

It is extremely difficult to unambiguously write down the control requirements in a document. Often textual descriptions in natural languages can be interpreted in various ways.

The domain expert who writes the requirements has a certain mental picture in their mind. However, software engineers responsible for realizing these requirements in the software implementation may interpret them differently after forming their own mental picture. There is often a big gap between the specification of the design and its implementation.

The documents may also serve as input or as a contract to a supplier to develop the control software. Then the impact and costs of ambiguity can be huge, much more so than when the implementation is done in-house within the company.

- Incompleteness and inconsistency

-

Besides the interpretation of the requirements also their completeness and consistency is important. Often the normally occurring situations (happy flow) is adequately covered by the requirements. However, the edge cases and exceptional circumstances are just as important, especially when safety is of critical importance to the system.

Consider for instance requirements for when the hardware fails, such as when a cable breaks or a sensor becomes defect. Such cases are often far more complex and the number of combinations/interactions that has to be considered can be immense. Ensuring that the textual descriptions of all these cases do not lead to inconsistencies is often practically undoable.

A good domain expert will be able to limit the number of mistakes, such as missing requirements and contradictions in the requirements specification, but typically can’t completely eliminate them. A good software/PLC engineer will surely spot some of the remaining mistakes during the implementation and testing of the controller.

However, even thoroughly tested and delivered industrial code often still contains faults. Furthermore, if the specification is incomplete, software engineers will make their own choices, which may or may not match with what the domain expert had in mind. Again, working with external suppliers, rather than doing the development in-house within the company, may aggravate these concerns.

- Multi-disciplinary systems

-

The multi-disciplinary nature of design versus implementation also plays a role. A domain expert may know everything about the functional requirements of the system. The software engineer, especially one from a supplier, may lack such knowledge. They come from different domains, often use different technical terms, and thus essentially speak different languages. This makes it more difficult for them to understand each other, and hinders communication.

- Abstraction levels

-

Furthermore, there is a difference in level of abstraction between design and realization. The control requirements are often written as functional specifications. For the implementation numerous details of a lower abstraction level play a role, such as data structures, message encodings and byte orderings. A functional specification typically does not concern itself with such aspects. Again, people from different disciplines and domains may not be able to effectively communicate with each other.

- Mixing design with implementation aspects

-

The situation becomes even more complex if (unintentionally) during the design also implementation aspects are incorporated into the functional specification. Then the clear separation between design and realization is lost. This often leads to more misunderstandings, which then requires more communication and collaboration to resolve.

- Outdated documentation

-

Another aspect to consider for specifications in documentation, is that any changes, such as bug fixes and new features, are often only implemented in the software. After a while the documents become more and more outdated and thus unusable. This increases the gap between specification and implementation.